“Two Sides”

For as long as I can remember, I’ve witnessed–on a local and national level–a political war. The two waging sides, aptly represented in terms of learning theories by exclusive behaviorists versus everyone else, are now as they have always been, fighting on the battlegrounds of public school classrooms. As we witnessed in 1954’s Brown v. Board and in 1987’s Edwards v. Aguillard, so we witness today the sweaty exertion to keep schools as they have been: synchronously operated factories aiming to produce dutiful factory workers by acting upon them like rats in a lab–or pigeons in a box (Skinner, 1947). Hammering against this seemingly self-regenerative wall of traditional behaviorism, learning theorists (e.g., Freire, 2009; Harel & Papert, 1991; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Lave & Wenger,1991; Piaget, 170) have and continue to assert some version of the same central claim: learners are not passive, contextless receptacles of knowledge. Rather, they are active, socially situated builders of knowledge–or, more often and more sinisterly– pedagogical victims of those who seek to deny and suppress this identity.

Good Little Youths

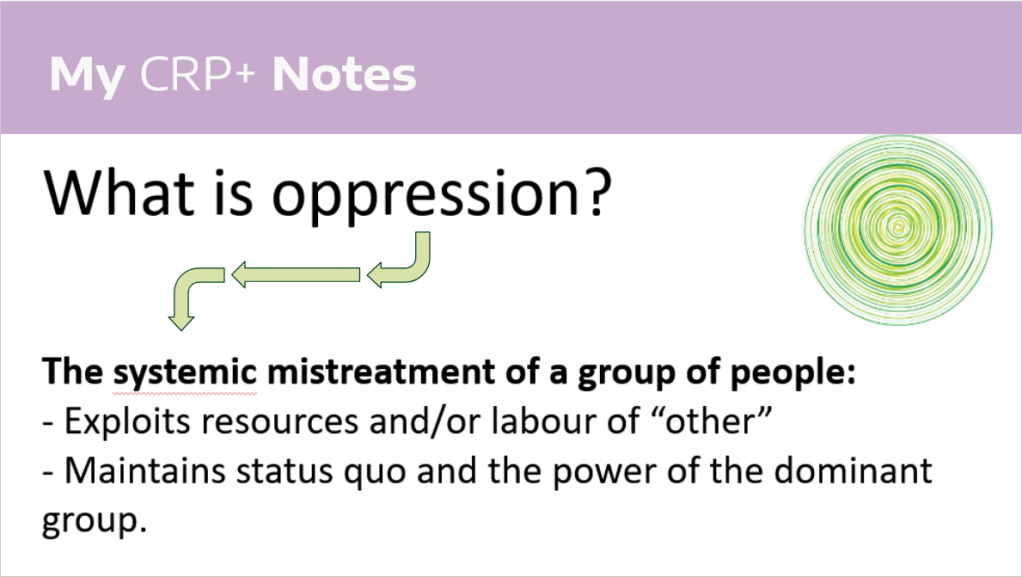

Although virtually no data suggests such methods will produce different results, schools proclaiming the goal of student achievement continue to operate as institutions of both classical and operant conditioning toward the end that young people submit to authoritarian leadership rather than be equipped to insightfully, democratically elect or become leaders in their own republic. In the case of classical conditioning (Pavlov, 1997), one could certainly argue that some conditioned pairings are pedagogically serviceable. Bells ring; hundreds of students are simultaneously triggered to feel immediate, if temporary, freedom to move, to attend to biological needs, to socialize with peers. Lights are flipped off; students felicitously self-silence, allowing for prompt, unhindered communication of, often helpful, directions. One the other hand, “Please stand for…” is immediately followed by children across the country putting hands over their hearts, turning toward a flag, pausing for the exact same fractions of a second after the exact same words, phrases, and clauses of a pledge without the implied punctuation but few if any of them could tell us how this response improves their lives in even the smallest way. On the contrary, such behaviors, as well as most of those conjured forth from their bodies via operant conditioning, are rarely, if ever, offered to the learners as objects to be examined for valuation. In the nearly unparalleled privacy of the quiet moment during many a child’s morning when they clothe their own bare bodies, they are reminded of their subjected position in relation to school and so make sure to pick up a school uniform shirt, dress code-sanctioned pair of shorts. African-American young people must consider if the way they are thinking of styling, managing, or covering their hair that morning will elicit a punishment in the form of a humiliating demand that they do otherwise. From the moment they set foot on school property, students are reminded by signs and posters of the behaviors they are not free to display, the ways they are not free to move their own bodies. Glittering displays announce the names of students elected to receive positive rewards in response to demonstrating desirous behaviors like compliance, quietness, and self-policing of time use. Foucault (1920) would vouch for the measurable effectiveness of these teaching strategies; Paulo Freire (2009), however, would question their ethical merits.

Everybody and Me

This is because, unlike B.F. Skinner, Freire belongs to the long list of psychologists and pedagogues who do not subscribe to the belief that behaviorism is the optimal means to the end of learning acquisition in schools. On the contrary, his unwavering commitment to problem-posing education is his prescription for any schools wanting to “stimulate true reflection and action upon reality” (Freire, 2009, p. 170) In disagreement with the behaviorist methodology of telling students when to speak and what to say, Ackerman (2001), defined real learning with marked similarity, describing it as “putting one’s own words to the world…finding one’s own voice…and exchanging ideas with others” (p. 2). Similarly, Ladson-Billings (1995), declared that civil rights workers were successful in the same endeavor precisely because they “ensur[ed] that the students learned that which was most meaningful to them” (p. 160) which she goes on to acknowledge is quite similar to the pedagogy of Freire. In contrast, to articulate her disgusted description of the U.S. federal government’s attempt to teach adult literacy through behaviorist authoritarian patronizing Ladson-Billings required one word: failure (p. 160).

Progressive Parallelogram

I could go on to present many startling parallels between these and other theorists’ seminal works, which never fail to echo the near identical refrain that authentic learning must be, in the end, about people in social relationships negotiating meaning between themselves and the real world around them. For now, I will close with this spectacular example of nearly exact parallel syntax. In 1991, Lave and Wenger argued that learning knowledgeable skills via the behaviorist model of teaching as response-stimulating action upon the learner must be “subsumed” [emphasis (and d) added] by participating in authentic sociocultural practice within these schools” (p. 29). Decades later and a continent away, Freire (2009) wrote that school learning happens when “knowledge at the level of doxa is superseded [emphasis added] by true knowledge, at the level of logos” (p. 170) These theorists do not mind hierarchy, but they prefer to use it when ordering approaches to school teaching by relative value, not when ordering learners by relative power.

References

Ackerman, E. (2001). Piaget’s constructivism, Papert’s constructionism: What’s the difference?. Future of learning group publication, 5(3), 1-11.

Foucault, M. (1920). Discipline & Punish. Random House.

Freire, P. (2009). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2(2), 163-174.

Harel, I. E., & Papert, S. E. (1991). Situating constructionism in I. E. Harel & S. E. Papert (Eds.), Constructionism (pp. 1-11). Ablex Publishing.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159-165.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Pavlov, I. P. (1997). Excerpts from the work of the digestive glands. American Psychologist, 52(9), 936-940.

Piaget J. (1970). Genetic epistemology. American Behavioral Scientist. 13(3), 459-480. doi:10.1177/000276427001300320

Saxe, J.G. (1873). The blind men and the elephant. Commonlit.org. URL

Skinner, B.F. (1947). ‘Superstition’ in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology. (38) 168-172.Vygotsky, L. S. (1979). Consciousness as a problem in the psychology of behavior. Russian Social Science Review, 20(4), 47–79.

Leave a comment